The events of the last two weeks in Myanmar bear considerable similarity to events a little over 19 years ago in a country that became synonymous with the abject failure of the UN, and defined the word “genocide” for the 20th century – Rwanda.

While the one million people butchered in Rwanda is a relatively small number compared to the almost two million killed during the reign of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, Pol Pot took four years to reach his tally while in Rwanda the figure was reached in 100 days.

The systematic murder, rape, desecration of corpses, destruction of homes, businesses and places of worship that have taken place against Myanmar Muslims of late closely parallel occurrences in Rwanda leading up to the shooting down of Rwandan president Juvénal Habyarimana’s plane on April 6, 1994.

Just like Myanmar President Thein Sein, Mr Habyarimana was a reformist, moderate president. His aircraft was returning to Kigalia with Burundi President Cyprien Ntaryamira on board following a meeting in Tanzania where multi-party elections that would end the Hutu dominated control of Rwanda had been discussed.

Rwandan president Juvénal Habyarimana Myanmar President Thein Sein – moderate and reformist. Photos: Courtesy Defense Imagery / Japan Times

Hard line opponents to the reforms that would have seen the Hutu (about 85 per cent of the population) sharing power with the Tutsi (about 14 per cent) included Colonel Théoneste Bagosora, directeur du cabinet (director of the cabinet, equivalent to chief of staff) in Rwanda’s Ministry of Defence, who had organised themselves into a secret “third-hand” inside the presidential palace.

As recently as Myanmar Armed Forces Day on March 28 the Myanmar Army declared that it has no intention of giving up the 25 per cent of parliamentary seats it reserved for itself in the Myanmar constitution, enough to give it veto power over any constitutional changes it doesn’t like – a 75 per cent majority in the parliament required to bring about change.

General Min Aung Hlaing said the military will continue to play a central role, both in politics and as peacekeepers in a country that has seen a surge of ethnic and religious violence in the two years since President Thein Sein’s administration began opening up the Southeast Asian country through a series of touted human rights and regulatory reforms.

The notion that the Myanmar Army will simply fade into the sunset and let the politicians rule (or tinker where they can from the shadows) in the same manner as the Indonesia army did in 2004 is fanciful.

Hard-liners: Rwanda’s Colonel Theoneste Bagosora & Myanmar’s General Min Aung Hlaing. Photos: Courtesy AFP / REUTERS/Soe Zeya Tu via Yahoo News

In Myanmar Buddhists and Muslims have led a generally peaceful coexistence for hundreds of years. Despite the years of oppression by prior Myanmar governments, up until June last year the Muslims, Rohingya and Buddhists in Rakhine State had traded and socialised with each other since the 1400s.

Suddenly mid last year the region became engulfed in what is politely termed “sectarian clashes” resulting in widespread destruction to Muslim parts of Sittwe and more than 125,000 displaced Rohingya and Kaman Muslims.

Most recently mobs of Buddhists led by people dressed as monks and armed with swords and knives have attacked and burned mosques, Muslim-owned businesses and schools, and incited mobs to murder and assault Muslim’s in Meikhtila resulting in at least 42 confirmed deaths.

In Rwanda the non-uniformed interahamwe (Literally: Those who work together) militia, trained in much the same way as local soccer teams do globally, though their “training sessions” were liberally sprinkled with a continual diatribe based on nationalism, Hutu pride, traditions, hatred, and increasing amounts of mock weapons and “combat training”.

At the end of their training sessions the Hutu interahamwe returned to their villages and neighbourhoods where they slept in homes adjacent to Tutsi neighbours and work colleagues.

Gunfire erupted in parts of Kigali almost as soon as the two surface-to-air missiles fired from the northern part of the Kanombe Military Camp, home to the presidential guard, the paracommando battalion, and the AntiAircraft Battalion, sent the president’s pane crashing in pieces into the grounds of the presidential palace.

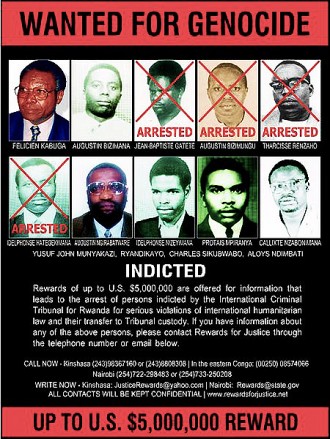

The world was prepared to spend money on bringing Rwanda genocide perpetrator to trial, but not prepared to stop the slaughter

Members of the Presidential Guard quickly erected roadblocks around strategic parts of Kigali to keep the UN peacekeeping force – United Nations Assistance Mission to Rwanda (UNAMIR) – led by Canadian Army Lieutenant-General Romeo Dallaire, the media and the 600-strong members of the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) at bay, while Hutu citizens emerged from their homes and began hacking and killing their Tutsi neighbours.

In Myanmar President Thein Sein has closed cities and districts by declaring a State of Emergency almost immediately upon unrest occurring, prohibiting travel to the region by foreigners and media, while the Myanmar Army has been despatched to bring about order with little international scrutiny.

While many international media representatives withdrew (or were withdrawn) along with the evacuation of foreign embassies and citizens almost immediately on the outset of the carnage in Rwanda, those who stayed were often ignored by Hutu intent on clubbing and hacking their Tutsi victims to death, including by the priests who took part in the slaughter of some 5,000 Tutsi seeking shelter in the Nyarubye Catholic Church.

In 1994 there were no digital cameras, everything was shot on negative or transparency film. Getting photos to publications was a case of asking someone leaving by air to carry rolls of film or negatives with them to London or Paris where a courier would be waiting for them. Communications was primarily via walkie-talkie, satellite phones, or the UNs phone network, though prior to April 6 1994 telex, fax and patchy international calls were available.

In the 21st century of digital images, mobile phones, internet, and social media, information is able to be disseminated considerably faster, while everyone who owns a modern smartphone is a potential “press photographer” and there is nothing more effective than a photo to illustrate – or to distort – a scene.

Of the 17 journalists and media representatives recorded by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) as having been killed in Rwanda in 1994, 83 per cent were local staff, while 43 per cent of the total had been abducted, taken captive or tortured prior to their deaths.

Last week the CPJ called on the Myanmar government to prioritise the safety of journalists covering “communal riots in central Burma”, citing reports by Radio Free Asia, the Democratic Voice of Burma, Associated Press, and The Irrawaddy of multiple incidents of news and camera crews being threatened, intimidated, and/or assaulted.

According to reports to the the CPJ: “armed Buddhist monks… put a knife to one journalist’s throat and seized and destroyed the memory cards… a Buddhist monk who covered his face placed a foot-long dagger at the throat of an AP reporter and demanded he hand over his camera…”

Shawn Crispin, the CPJ’s senior Southeast Asia representative said: “We condemn the threats and intimidation of journalists covering the recent communal riots in Burma. Authorities are obliged to ensure the security of journalists working in conflict areas”.

Authorities are also obliged to ensure the safety and security of ALL of their citizens – but wait, the Rohingya are not Myanmar citizens under the country’s constitution – despite evidence of early Bengali Muslim settlements in Arakan dating back to the 1430s.

Satelite images of part of Meiktila, Myanamr showing before and after the March 2013 violence against Muslims. Photo: Courtesy Human Rights Watch

In Rwanda the Hutu commonly referred to the Tutsi as cockroaches or worse and there is no shortage of evidence that similar phrases are used in Myanmar by those intent of sowing division. In particular the Burmese word “Kalar” (“nigger”) is used by some monks and Buddhists to refer to Myanmar Muslims.

Prior to the downing of the Rwandan presidents plane the increasing number of attacks against Tutsi in rural Rwanda were ignored by many in Kigali, where freshly baked crusty french bread and baguettes were consumed with imported French butter, preserves, and cheeses and washed down with robust coffee by foreign embassy staff and NGOs in sidewalk cafes, villas and compounds.

Around Kigali privateers intent on establishing business in the tiny central & east African country darted from meeting to meeting, agency to agency in much the same way as those seeking to do business in the newly opened frontier of Myanmar do today.

The swimming pools at major hotels including the Hôtel des Mille Collines were well patronised by mostly European visitors and more than a few families, while bureaucrats, UN staff, and NGOs organised a never ending round of seminars, gab feasts and social functions, while just out of sight tensions simmered.

Buddhist monk Saydaw Wirathu fuels violence

In Myanmar a speech made by Buddhist monk Saydaw Wirathu at Mandalay’s Ma-soe-yein teaching monastery is said to have fuelled the ferocity of the most recent round of violence against Myanmar Muslims in Meiktilla, and helped spread it to other regions.

Arrested in 2003 for distributing anti-Muslim literature, in his most recent video / statement Wirathu, the leader of a new ultra-conservative, right-wing, nationalist movement known as 969, calls on Buddhists to join the 969 Buddhist nationalist campaign by doing business or interacting in any way with people who are “not of our kind: the same race and faith”.

Throughout the 1994 Genocide Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM) broadcast continual propaganda against the Tutsi and moderate Hutus, directing gangs of Hutu interahamwe to locations where Tutsi were seeking shelter.

A 2012 Harvard University study by David Yanagizawa-Drott suggests that approximately 50,000 deaths were caused by the station’s broadcasts, which also was responsible for recruiting up to 9.7 per cent of the people who took part in the killing.

Despite the desperate pleadings of UNAMIR Force Commander General Dallaire, the head of the International Committee for the Red Cross, Philippe Gaillard and numerous agency and freelance photographers and journalists, world leaders such as former US president Bill Clinton, then American Ambassador to the UN Madeleine Albright, and the head of the UN Peace Keeping Operations (UNPKO), who later became UN Secretary-General, Koffi Annan, all maintain they were unaware of the severity of what was taking place in Rwanda at the time.

In fact Mr Annan specifically ordered General Dallaire that he could not dig up interahamwe arms caches he had been told about in the days leading up to the assassination of president Habyarimana, and instructed UNAMIR PKF that they were not to use force and tightened the terms under which its members could return fire to defend themselves.

The only way that Messrs. Clinton, Albright, Annan, et al could not have been aware of the full extent of what was happening in Rwanda in 1994. Graphic: Supplied

The only way that Messrs. Clinton, Albright, Annan, et al could not have been aware of the full extent of what was happening in Rwanda in 1994 was if they each had their heads embedded securely in a place where the sun doesn’t shine. The truth is that none of them wanted to know what was going on in Rwanda in 1994 as to publicly acknowledge the genocide taking place would have required they take intervention action.

It’s a matter of history that despite thousands of gruesome photos of dead and severely injured Tutu, thousands of words written about what was happening and hundreds of hours of radio and television reports, it took the US State Department more than 83 days before it used the word “genocide” in connection with Rwanda and only then prefaced by the the words “acts of”.

On the sidelines of an Asean 2020 seminar hosted by the Future Innovative Thailand Institute in Bangkok on March 22, Dr Termsak Chalermpalanupap, the former Asean director of political and security cooperation said “there is no Rohingya problem in Myanmar as long as Myanmar says there is no Rohingya problem”.

A visiting Research Fellow on political and security affairs at the ASEAN Studies Centre, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore, Dr Termsak said, “the Rohingya are not an Asean problem… Asean will not and should not get involved”.

While no-one is suggesting the number of deaths from the violence against Myanmar Muslims is anywhere near that of Tutsi killed in the 1994 Rwandan genocide, the 2015 elections are still some way off, metaphorically though only in the same way as the Rwandan presidents plane was some way off before it departed Dar es Salaam on April 6, 1994.

As Myanmar rockets towards full multi-party elections in 2015 and the first chair of the Asean Economic Community (AEC), the big concern for many is that opposition leader and activist Aung San Suu Kyi, who has to date remained all but mute on the killing of Myanmar Muslims and Rohingya, will continue to say nothing in pursuit of her ambition for presidency… a position she is constitutionally barred from occupying.

Ends

© 2013 John Le Fevre

© 2013 John Le Fevre

Rwanda genocide • Myanmar genocide • Muslims • Buddhists • Rohingya • Asean • UNAMIR • Burma •

John Le Fevre

Editor at Photo-journ.com

John Le Fevre is an Australian national with more than 25 years' experience as a journalist, photographer, videographer and copy editor. He has spent extensive periods of time working in Africa and throughout Southeast Asia and previously held senior editorial staff positions with various Southeast Asia English language publications and international news agencies. He has covered major world events including the 1991 pillage riots in Zaire, the 1994 Rwanda genocide, the 1999 East Timor independence unrest, the 2004 Asian tsunami, the 2009 Songkran riots in Bangkok, and the bloody 2010 red-shirt protests in Bangkok. In 1995 he was a Walkley Award finalist, the highest awards in Australian journalism, for his coverage of the 1995 Zaire (now Democratic Republic of Congo) Ebola outbreak. In addition to news and feature writing he also writes for commercial websites and performs SEO, SNM, and SEM services at Pattaya Web Services

Read more: Is Myanmar another Rwanda genocide in the making? http://photo-journ.com/is-myanmar-another-rwanda-genocide-in-the-making/#ixzz2Sxj8mm3P

No comments:

Post a Comment

thank you..moderator will approve soon..your email will not be published..